Harish Damodaran

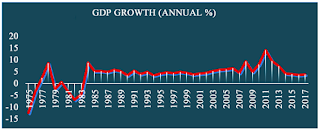

Sharp and protracted economic slowdowns aren’t new to India. Since

Independence, there have been at least eight episodes of significant GDP

growth rate declines over two years or more — 1961-62 and 1962-63,

1965-66 and 1966-67, 1971-72 and 1972-73, 1984-85 to 1987-88, 1990-91 to

1992-93, 2000-01 to 2002-03, 2012-13 and 2013-14, and the current one

from 2018-19.

The slowdowns till the Eighties were mostly a result of

drought-induced agricultural contractions, wars or balance of payments

(BoP) pressures. Shortage of foreign exchange for imports, even of

essential materials or components and spares used in capital goods,

besides austerity measures introduced after the 1962 Sino-Indian War,

caused the first growth dip episode. Back-to-back droughts and a BoP

crisis leading to the 36.5 per cent rupee devaluation of June 1966,

likewise, precipitated the second downturn, while it was a combination

of the 1971 Indo-Pakistan War and the 1972 famine in the case of the

third. The Eighties saw three consecutive drought years — 1985, 1986 and

1987. Its impact on the broader economy was predictable, given the farm

sector had a roughly one-third share in India’s GDP even at this point

in time.

Only during the past three decades has agriculture’s role in bringing

down or pushing up overall growth diminished relative to other

macroeconomic factors. Thus, both the early-Nineties slowdown and the

one in the last two years of the United Progressive Alliance (UPA)

regime were preceded by “twin deficits” — on the fiscal and external

current account fronts. The growth slump of the early-2000s during the Atal Bihari Vajpayee-led

National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government had mainly to do with the

aftereffects of the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the sanctions imposed

by the US and other countries following the 1998 Pokhran nuclear tests,

and the end of a mid-1990s corporate-driven mini-investment boom.

The current slowdown — GDP growth has dropped in every quarter from

January-March 2018 down to July-September 2019 and showing little signs

of recovery — is unique by contrast.

Firstly, it has taken place amidst remarkable political stability,

with the unquestioned leader of a single-party majority government at

the helm. This was not so with the UPA, Vajpayee’s NDA or the 1991

minority Congress government of Narasimha Rao. Narendra Modi’s popularity is probably rivaled only by Indira Gandhi.

But she was a relative novice as prime minister during the 1966

devaluation and emerged as a truly strong leader only after the 1971

general elections, which were held before the economy went into a

tailspin. One could similarly argue that Jawaharlal Nehru was well past his prime when India’s first major downturn happened. That leaves only Rajiv Gandhi, who took over after his mother in 1984. However, he never enjoyed the cult status or credibility that Modi today commands.

Secondly, this slowdown isn’t courtesy the usual “F” suspects — food,

foreign exchange and fisc. Not only does agriculture account for hardly

15 per cent of India’s GDP now, annual consumer food price inflation,

too, has averaged a mere 1.59 per cent between October 2016 and October

2019. There has been no BoP crisis either; foreign exchange reserves

were, in fact, at a record $448.60 billion as on November 22. The Modi

government may have deviated from the original schedule of reducing the

fiscal deficit to 3 per cent of GDP, but the average figure of 3.7 per

cent for 2014-15 to 2018-19 is much better than the 5.4 per cent during

the previous five years under UPA.

The Modi period, if anything, has been marked by both political and

macroeconomic stability. Nor has it been witness to “external”

disruptions in the form of wars or oil price surges. Even the US-China

trade conflict from 2018 is not comparable in its effects on the Indian

economy to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis or the 2013 “taper tantrum”.

In any case, it’s not as though India’s exports were really booming

before 2018.

Unlike all the earlier downturns whose precursors/triggers were

supply-side constraints in food and forex, macroeconomic imprudence or

external shocks, what we are now experiencing is more of a

“western-style” slowdown exacerbated by internal policy misadventures.

At the heart of it has been the twin balance sheet (TBS) problem — of

debts accumulated by private corporates during the investment binge of

2004-11 turning into non-performing assets of mainly public sector

banks. A similar bad loan build-up did take place even in the mid-1990s,

forcing the subsequent cleanup of bank balance sheets and deleveraging

by India Inc that also impacted growth during the Vajpayee government

period.

But the difference between then and now is how the TBS problem,

despite being flagged way back in December 2014 by the former chief

economic adviser, Arvind Subramanian, has been allowed to fester – and

spread to sectors such as non-banking financial companies and real

estate that have far more contagion effect than steel, power or

textiles. Even worse is the self-inflicted wounds from demonetisation

and the unprepared rollout of the goods and services tax (GST), hitting

those who were least responsible for the TBS problem: Farmers, petty

producers and MSMEs. Job and income losses in the informal sector has,

in turn, depressed consumption demand, including for the products of

listed firms and other organised players that were supposed to have

benefitted from demonetisation and GST.

If indebted corporates, risk-averse banks and the more recent credit

crunch resulting from defaults by the likes of IL&FS, Dewan Housing

Finance and Altico Capital — these are threatening to spill over to

other financial and real estate-linked entities — have come in the way

of investment demand picking up, consumption also taking a hit makes for

a gloom-and-doom narrative.

The irony, of course, is that all this comes at a time of great

political as well as macroeconomic stability. This is, indeed, a

first-of-its-kind slowdown in India, where food, foreign exchange, oil,

war and other “supply-side/external” factors have had no role. And if

economic history is any guide, Western-style slowdowns, which are

largely about crisis of confidence, sentiment and “demand”, tend to be

long-drawn-out affairs. Controlling inflation may be easier than getting

consumers to spend and firms to invest.

This article first appeared in the print edition on November 30,

2019 under the title ‘A different downturn’. Write to the author at

harish.damodaran@expressindia.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment